Sowing Sustainability Through Chicago’s Seed Libraries

Deep in the doldrums of another frigid Chicago January, it’s an exciting time for one particular group of residents, who are busy gathering and exchanging the season’s hottest commodity. Rarely larger than a nickel, they’re collected all over the world. You need a permit to transport some kinds between countries, but you can buy others for mere cents at a hardware store. When cared for correctly, they’ll appreciate in value by an order of magnitude in less than a year. They’re not diamonds or pills – they’re seeds, and winter is the perfect time to collect them.

The tradition of seed sharing has been around since the dawn of agriculture, and the practice is alive and well in Chicago, if you know where to look. There are more than 20 “seed libraries” located throughout the city, which are exactly what they sound like: physical collections of seeds that are available for community members to take and plant in their own gardens. They’re more common than you might think and the crops they yield are just as diverse and vibrant as the community they foster.

The seeds from seed libraries come from many different places. The seed library at the Edgewater Branch of the Chicago Public Library, for example, gets some from individuals who harvest seeds from their own garden, and solicits specific types from larger organizations.

“I asked the Field Museum for some native plants specifically,” said library branch manager Joanna Hazelden. “People will take whatever seeds you have, so I wanted to help people pick stuff that is native to the area.”

Stored in a small set of green plastic drawers next to the front desk, Hazelden grows tomatoes and basil in a hydroponics system next to the seeds, which piques visitors’ interest and introduces hydroponics to those who don’t have the outdoor space to grow plants from soil. Being inside an actual library, Hazelden, of course, displays gardening books next to the seeds, and hosts educational events that attract both novice and experienced gardeners alike.

She says their setup provides library visitors with a friendly and accessible way to get into gardening.

“Getting seeds from our seed library can feel more low-risk,” Hazelden said. “People can come here to get seeds and try something new, as opposed to getting overwhelmed in a large nursery.”

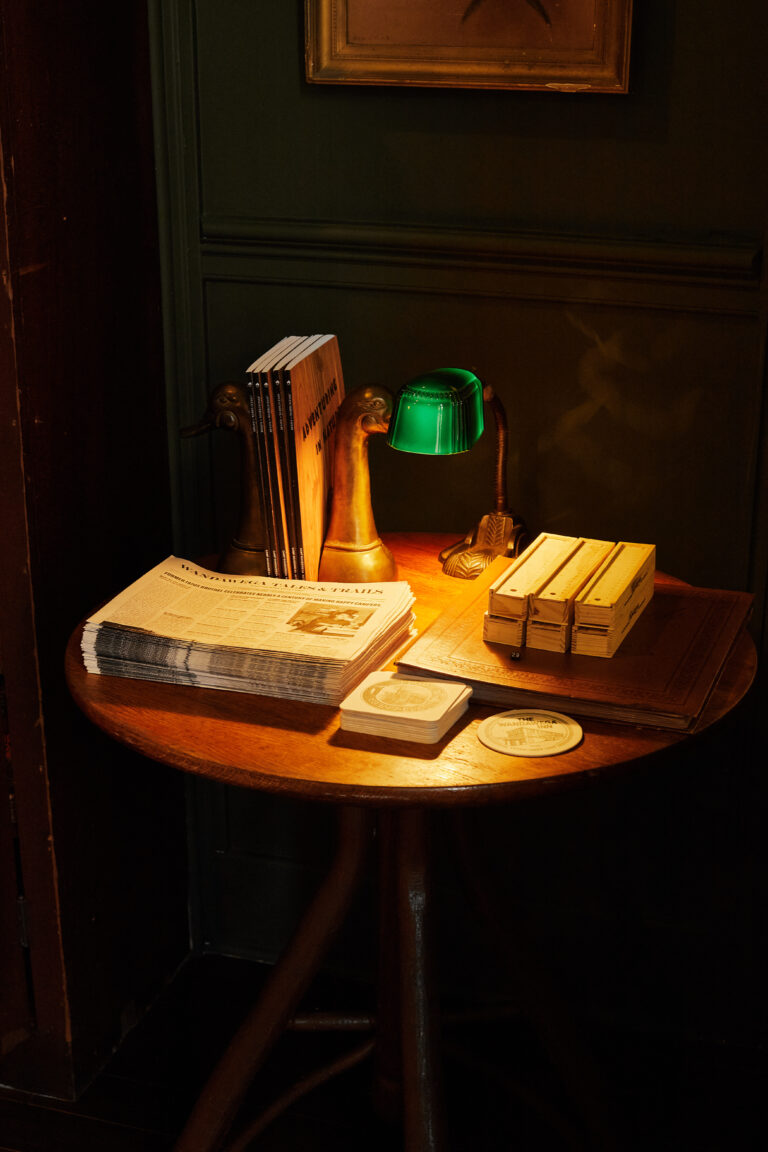

Other seed libraries will exchange seeds through seed swaps, where the community can bring their own seeds to give out and take others. Kept in a recycled suitcase – a testament of their commitment to sustainability and creative reuse – the University of Illinois Chicago’s Heritage Garden seed library travels across the city to distribute seeds and gardening knowledge at different events.

“We call it a seed swap, but really, we’re just giving them away,” said Sarita Hernández, program director of the Heritage Garden.

As a joint effort between each of UIC’s cultural centers, the Heritage Garden seed library makes an effort to include culturally relevant seeds, so that those from different backgrounds can grow crops they’d naturally cook with – yuca instead of Russet potato, for example.

“We have seeds like Palestinian watermelon, different variations of corn, and Vietnamese pepper,” said Jeshaun Creswell-Jones, junior in biology and senior leader at the Heritage Garden. “We’ll take suggestions from the other cultural centers for what seeds to get.”

Seed libraries have several advantages over nurseries and hardware stores. They’re free and often have an educational component, which can make for a low-risk entry point to gardening, as Hazelden points out. They also address environmental concerns, including the genetic integrity of mass-produced seeds and biodiversity loss. The resulting fruits and vegetables can also offer nutritional benefits, and can be more interesting to cook with than standard grocery store produce.

For the worker-founders of Englewood-based Cooperation Racine, the aim of their Harvest Seasoning seed library and story-banking project was to build community through food. Each seed packet comes with a QR code through which visitors can listen to recorded conversations with neighborhood elders as they share their personal stories and experiences with gardening.

“We see the entry point to gardening being these stories around food as a way to connect with people,” said Saleem Hue Penny, member of founding Worker/Owner Team at Cooperation Racine, LWCA. At a time when residents have to leave the neighborhood to access the nearest grocery store, Hue Penny says the seed library’s collaborations with Englewood community gardens are critical.

“Being able to supplement your staple groceries with fresh produce is the dream when thinking about solidarity,” he said. “Food, and being able to feed yourself and your community, is at the heart of any movement.”